In 1976, William Smithers sued Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for multiple violations of his contract with defendant’s television program Executive Suite.

In 1976, William Smithers sued Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for multiple violations of his contract with defendant’s television program Executive Suite.

The litigation included assertions that MGM’s television chief Harris Katleman had, in conversation with Smithers’ theatrical agent, threatened that, should Smithers pursue the matter, Katleman would be hard pressed to recommend Smithers for future employment with CBS, the network airing Executive Suite.

At first, Smithers had caved to this threat, but when the violations were repeated despite his protests, he, though advised by counsel he could endanger his career, decided to take action.

Smithers alleged Breach of Contract, Tortious Breach of Contract and Fraud. His contract – actually a “memo of understanding” never formalized – had specified that with three named exceptions, no other cast member could receive more money or better billing than he.

As cited, this provision was violated several times. At significant issue was whether starring billing was worth money, since the plaintiff sought monetary recompense.

(In the several-year period leading up to actual trial, Smithers kept a record of relevant and significant memories on an audio tape. Attorney David Frank, In a phone call, asked Smithers if he had any material that could be useful in preparing the case.

Smithers in that call referred to the tape and promised to place it next day in the mail box at the curb of Frank’s house.

Though the local mailman remembered seeing it in that box when he delivered Frank’s mail, it was never thereafter found by Frank or any known person.

Had Smithers’ phone been tapped? He never knew.)

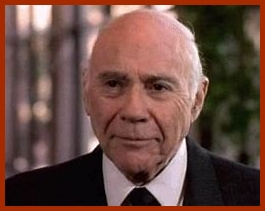

Testifying for Smithers as expert witnesses on the relevant monetary issue were the Executive Secretary of the Screen Actors Guild; the casting director for QM Productions, producer of such TV series as The FBI and Barnaby Jones; Smithers’ theatrical agent at the William Morris Agency; and character actor John Randolph.

(Earlier, character actor Will Geer had volunteered to testify for Smithers, but Geer died before trial began. Smithers, via personal letter or personal visit, had also sought – unsuccessfully – to enlist as expert witnesses: Steve McQueen, Buddy Ebsen, Jack Klugman, Ralph Waite, a casting director at Universal Studios and one of the producers of Executive Suite.)

MGM was represented at trial by Wyman, Bautzer, one of most prestigious law firms in Los Angeles; Smithers, by his best friend David Frank, a former actor then two years out of law school.

The trial took three weeks. On each allegation, only a 9-3 majority – not a unanimous vote – was required of the jury.

(Jury members obviously enjoyed the lively, articulate testimony of John Randolph, whom they’d seen in films and on TV. Randolph is the only trial witness many have ever seen who, at the conclusion of his testimony, stood up, leaned over and shook hands with the judge.)

During the tense wait while the jury deliberated, Frank advised Smithers to remain at the courthouse during each day and to have lunch in its cafeteria (where jurors ate) so that jurors would see that Smithers cared about the result. On one of these days Smithers and Frank were notified that the jury had a question for the judge.

“Is it permitted,” they asked, “to award Smithers more than he has requested?”

The answer was “Yes.” The jury award was substantial.

MGM appealed this decision all the way to the California Supreme Court. For various and complex reasons, this resulted in a delay of four years.

Frank had offered his services to Smithers as “pro bono,” meaning in this instance no fee if the case failed, but a percent of the award should there be one. But Frank needed money to sustain document and other costs during the lengthy appeals.

Smithers’ fiancé, a neighbor-friend and his father – all – loaned him substantial amounts to provide for escalating appeal expenses. These loans were eventually repaid at about 15% interest – par for that time – except in the case of his father who refused more than 5% interest.

(Smithers had planned, should a monetary award fail entirely, to sell his home to repay the loans.)

The trial had received considerable publicity: The Los Angeles Times featured an interview, with photo, on the front page of its Sunday “Entertainment” section.

For several years following trial, Smithers was not employed, seeming to confirm the prediction given him by a producer and a casting director that he might “Win the battle, but lose the war.” Some fellow actors asked sweetly, “Do you think you’ve ruined your career?”

His career, as it turned out, had only been temporarily stalled. It was substantially revived when he was chosen for the recurring role of Jeremy Wendell in the original series Dallas.

In 1980, at long last, all courts had affirmed the original jury verdict. The actual MGM check arrived the same week Smithers walked onto the Dallas set after broadcast of the series’ notorious “Who Killed JR?” episode.

In 1980, at long last, all courts had affirmed the original jury verdict. The actual MGM check arrived the same week Smithers walked onto the Dallas set after broadcast of the series’ notorious “Who Killed JR?” episode.

Smithers vs. MGM is now taught in Entertainment Law classes in law schools.

REFERENCES:

-

“1983 California Courts of Appeal Survey – Entertainment Law. I Contract-Related Cases – Smithers vs. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayor [sic] Studios, Inc”.

-

Law and Business of the Entertainment Industries, pp. 463–464.