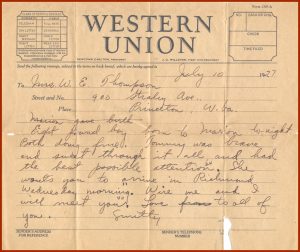

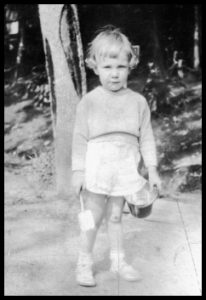

William Smithers was born July 10, 1927 in Richmond, VA (as Marion Wilkinson Smithers, Jr.) to father Marion Wilkinson Smithers and mother Marion Thompson Smithers. (Three Marions? Despite this, I was always called Bill.)

My father, an electrical engineer, got a job with Western Electric in New Jersey, but lost it in the Great Depression, after which we moved for months into the home of his parents in Richmond. There were nine of us, including two uncles and two aunts.

My father worked for his father as a house painter and wall-paperer. Family legend has it that my mother wheeled me around in a baby carriage as she sold can openers to make a little money. When old enough, I attended William Fox grammar school. I can remember pleading with my mother to allow me to walk the five blocks to school by myself. Finally, she said “OK,” and on the appointed day I set out proudly on my trip. When I crossed the final street to the school playground, I happened to turn around. There on the other side of the street was my mother. She had followed me the whole way!

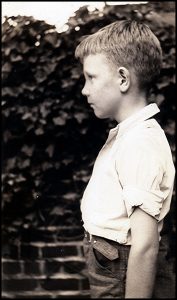

At Fox school there was a “Fresh Air” class for the puniest students, including guess who? In this class, at lunchtime a student was sent to buy soup and milk. The blackboards were then rolled away to reveal a stove that heated the soup. After our lunch, folding cots were brought out from behind the blackboards and we all had to have a half-hour nap. My cot was often near a low book shelf and frequently I would sneak a book to read surreptitiously instead of dozing.

In this school system promotions were made every half-year, and it seemed I was smart enough to be granted a semester skip-ahead in fourth grade.

In 1936 my father got his job back with Western Electric and we moved finally to Elizabeth, New Jersey.

There I attended Robert Morris grammar school. It turned out that the educational system in New Jersey was so far advanced over what I had known in Virginia that, though I had skipped a half-grade in Richmond, in Elizabeth I was required to repeat fourth grade.

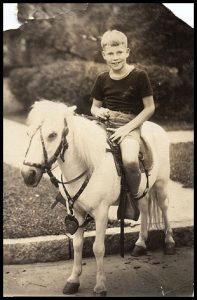

An itinerant photographer offered

a pony-sit to get some business.

He succeeded.

A group of classmates at Robert Morris. Note the knickers, standard kids’ pants-wear at the time. Smithers, in shorts, still puny. While playing ball in this school playground one afternoon after class, we stopped to watch a large dirigible pass high above in the sky. It was the Hindenburg, on its way to a burning crash in Lakehurst, NJ!

My acting career began here, playing the Lord Mayor of London in the school operetta “Around the World in an Airship.”

“Oh, I’m the Lord Mayor of London town,

A very large city of great renown.

And if you’ve respect for my cap and gown,

A welcome I”ll give to you!”

Graduating to Alexander Hamilton Junior High School, I – inexplicably – contributed to the school paper’s joke column; played first base with the Elmora Panthers (a team composed of rejects from the school A Team); played an End Man in the seventh-grade minstrel show (we actually put on black-face!); was the 17th to fall in love, unrequited, with fatal beauty Ginsy Horning; kept track on a map for civics class of the battle-lines of the German-Soviet war in Russia; and played a lead in the ninth-grade operetta along with Phyllis Kirkgaard, later to star in MGM films as Phyllis Kirk.

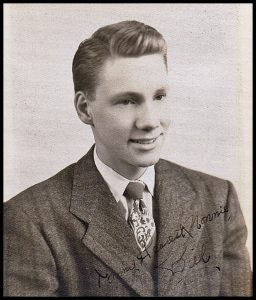

High schools in Elizabeth, NJ were not then co-ed. For boys there was Thomas Jefferson; for girls Battin High. Here I learned all nicknames of the Brooklyn Dodgers to keep up with classmates; attended the Teenage Night Club Monday evenings where we danced to records in a church gym – keeping teens off the streets and out of trouble while their parents worked factory night shifts for the war effort; was lucky to have several friends: my best buddy Chas Londa (who became an oil company exec in the Middle-East); Alex Hoagland (friend to everyone, class president, who became head of his law firm’s branch in Mexico City); and “The Swede” Bob Johnson (who years later died prematurely as a priest in Chile); edited the senior year book; and joined with Battin girls to put on plays such as “Stage Door,” including the aforementioned Phyllis and me.

In my senior year the war in Europe ended.

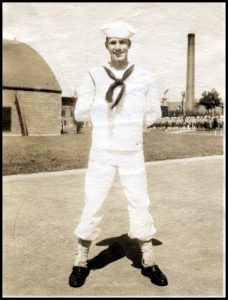

This was May, 1945. The war with Japan was still on. Though I had been called Bill all my life, it was only now, before I volunteered to join the Navy, that I officially changed my name to William Wilkinson Smithers. I entered the Navy’s radio technician program with rating of Seaman 1st Class and was sent to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station: “Boot Camp.”

In August, 1945, after atomic bombs had obliterated the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, World War II ended. The Navy no longer had use for radio technicians. Apparently, it was legally obligated to give its registrants a year’s training, so we were offered, if we signed out, duty at the discharge centers nearest out homes. Accepting the offer, I was assigned to the Long Beach, Long Island separation center, and spent a year as a Guide, conducting groups of sailors through the three-day process of leaving the service.

After 14 months in the Navy, never even having boarded a ship, I was mustered out myself. I wanted to go to college but didn’t know where. The Richmond uncle who had been my pal as a kid recommended Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia. There I went.

Once again I was in an all-male school, with the all-female State Teachers’ College seven miles away in Farmville. Here I got good grades until I became seriously smitten with STC student June Walsh; studies somehow became secondary. In the joint HSC-STC drama club I played Petruchio in “The Taming of the Shrew,” Sheridan Whiteside in “The Man Who Came to Dinner,” and Prince Sirki in “Death Takes A Holiday.”

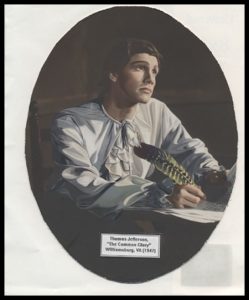

Producers in Williamsburg, VA were planning a tourist attraction to begin the summer after my freshman year: “The Common Glory,” by Paul Green, a “symphonic drama” about the Founding Fathers, to be presented in an outdoor amphitheater outside Williamsburg. The lead, Thomas Jefferson, and the Narrator were to be played by professional New York actors; the supporting cast by Virginia college students. I auditioned and was cast as British parliamentarian William Pitt (The Younger) and as understudy for Jefferson.

Days after rehearsals began, the producers decided they didn’t like their New York choice for Jefferson. The role was given to me, age 19. I turned 20 during that summer’s performances.

The Assistant Director, a teacher at Northwestern University, invited me to join the next year’s summer theater group in Eaglesmere, Pennsylvania, led by the notable Alvina Krause.

I now began to think seriously about what career I would choose. After some consideration I decided to risk it all, transfer for junior and senior years to Catholic University in Washington, D.C., which had a reputable drama department, and asked June to marry me with that plan in mind. She said “Yes,” though it meant she would have to abandon college plans and go to work.

Announcement of these marriage plans at home evoked from my mother: “Don’t think we’re going to support you.” In fact financial help from the now-famous GI Bill, June’s work with a government agency in D.C., and a bit from my job at the university’s library, would get us through my third college year.

Catholic U’s drama department was headed by the dynamic Father Hartke. In this part of the universe Walter Kerr, teaching Drama Theory at the graduate school, was a god. Students all quoted what “Walter” said about this or that. Kerr later became

theater critic for the New York Herald Tribune. He was also a playwright, as was his wife Jean, who was to write several Broadway hits, including Mary, Mary.

Neglecting part of my studies, I spent much time in rehearsal for “Romeo and Juliet” (Romeo); “King Lear” (Edgar); and Shaw’s “Arms and the Man” (Nikola). My classmates included the bold-as-brass Ed McMahon, later to become Johnny Carson’s ”’sidekick,” and Phillip Bosco, who later starred in the Broadway play “Copenhagen.”

At the Eaglesmere, PA summer stock playhouse the following summer, I shared acting and set-building with the other college actors, including Hank McKinney, later to become film star Jeffrey Hunter.

As the fourth year of my college days came to an end, I would not graduate, having failed several courses. I decided not to return for a degree but to press on in hope of a career. Driving a used car I had bought from a student, June and I spent the summer of 1950 at the Henrietta Playhouse in Rochester, New York, then rested for a few days at my parents’ home in Elizabeth.

In October, 1950, June and I, with everything we owned piled in the ’39 Plymouth and $100 in cash, drove into New York City to find what life would offer – both scared to death. June found a job as secretary; I found a job as an usher at the Alvin Theater where “Mr. Roberts,” starring Henry Fonda, was playing. Night-time employment enabled me to “make the rounds” during the day.

Trade papers announced that producer Dwight Deere Wiman was producing Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” to star Olivia de Havilland. Only those who had acted in this play somewhere were to be considered for auditions.

Along with perhaps thousands of others, I sent in my picture and resumé – and heard nothing. I began to run into former C.U. classmates who said they had gotten auditions for the play. One day I ran into one such, a particularly pompous guy who let me know with smirking satisfaction that of course he had got a reading for the play. “Gee, you haven’t?”

Unknown to us both, he had created my future.

On fire internally after this encounter, I marched to the office of producer Wiman and entered to find it empty except for a receptionist. “Can I help you?” “I’d like to speak with Miss Abarbanell [casting director].” “She’s out to lunch.” “I’ll wait.” “Well she won’t see you.”

I then burst into an impassioned plea, half in anger, half in tears. “You said only those who’d acted in the play can be considered. I played Romeo in school. I have a good record of performance in my life. Newcomers like me should at least be given a hearing. Everyday people come up from the streets to make good in this profession. You know that! All I’m asking is a chance!”

This wonderful lady looked long and hard at me. She could have thrown me out. Instead, she said, “If I connect you on the phone now with Miss Abarbanell, will you tell her what you’ve told me?” “Yes.” “Good – I think they ought to be told that once in a while!”

Miss Abarbanell was equally kind: “We mean no insult to you, Mr. Smithers. We sometimes feel overwhelmed with audition requests. You seem to have a good record. If I arrange a meeting with the Assistant Director, will that satisfy you?”

The Assistant Director questioned me for some time, then said, “The only appropriate role that hasn’t been cast is Benvolio, If you like, I’ll arrange an audition with Mr. Glenville.”

Intensely excited, as you can imagine, on the scheduled day I walked out onto the theater stage to audition for director Peter Glenville. When I had finished, there was a silence in the auditorium. Then Mr. Glenville asked, “Do you know anything from Shakespeare by heart?” “Yes, the Chorus from Henry V.” “Let’s hear it.”

Did that. He came up on the stage. “Would you try that again without attempting an English accent? Just use what comes naturally to you.”

Did that. Discussion among people in the seats. “Mr. Smithers, would you take a look at the role of Tybalt and come back to us?”

Either that day, or whenever it was, I re-appeared on that stage and read for Tybalt.

Again, a brief silence. Discussion among people in the seats. “Allright, Mr. Smithers, thank you very much.”

As I was walking off, Mr. Glenville said, “Oh, Mr. Smithers. If we cast you in this part, would you be willing to dye your hair red?”

“You can dye it green!” Laughter.

I got the part.

(Part 2)

The New York Years (1950-1965)

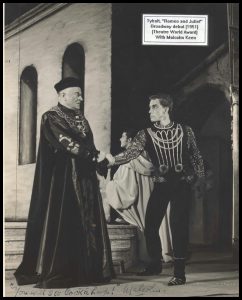

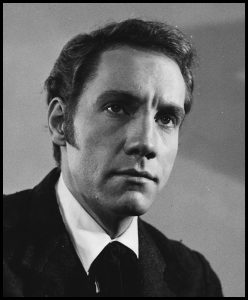

The Dwight Deere Wiman production of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, starring Olivia de Haviland, directed by Peter Glenville, and in which I had been cast as Tybalt, was not well received by critics; it closed in a matter of weeks.

But I did receive some of the best personal critical reviews, and was designated by Theatre World magazine one of its “Promising Personalities of the Year”: actors who had given notable debut performances on and off Broadway.

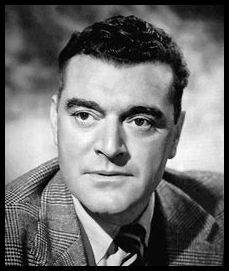

Well-known British actor Jack Hawkins, who had played Mercutio, kindly recommended to his US agent that she take me on for representation.

In that year June and I dissolved our marriage. We had been living in a small apartment in New York City that looked out over an elevated railway.

I moved to a rooming house on East 46th Street. The room, 7 ½by 17 feet, was above an Indian restaurant. It cost $7/week and had one bathroom for three rooms on that floor.

Unemployment insurance was available to “between jobs” actors then. You had to go personally each Monday to the UI office to get your cash money. My memory is that by Sunday I sometimes had fifty cents left, so slept late to minimize hunger pangs, then went to the local greasy spoon for pancakes which filled me up for the rest of the day.

The following year I was cast in Jean Anouilh’s Legend of Lovers, starring Richard Burton and Dorothy McGuire. “The Hotel Waiter,” a small role, was a smarmy seedy hotel waiter who sought every opportunity to spy on the passionate lovers. (See photo album.)

During one rehearsal, Burton said to me, “You’re going to be a star. You know how to take your time on stage.” (The rest is not history.)

In 1952, Jo Rabb, an actress friend who had been one of the Chorus in Romeo and Juliet, asked me to be her partner for her audition for the Actors Studio. In those years it was popular for actors to do scenes from novels and short stories. We prepared a scene from Nelson Algren’s The Man With the Golden Arm.

For acceptance into the Studio’s famous – and free – domain, one had to pass two auditions: a preliminary judged by three experienced Studio members; then a “final” judged by the organization’s directors: Lee Strasberg, Elia Kazan and producer Cheryl Crawford.

We passed the preliminary. The Studio secretary asked that we make the final a joint audition, that is for both of us. I agreed.

I passed the final; Jo didn’t.

My experience in the Actors Studio has been a fundamental influence on my work for the rest of my career.

The meaning, and significance, of “The Method” approach to acting and directing as originated by the Russian theater practitioner Constantin Stanislavsky and promoted in various ways in the US by Lee Strasberg, Harold Clurman, Sanford Meisner, Stella Adler and others, is so complex and so often misunderstood, that I hope eventually to devote a special section elsewhere in this memoir to my understanding and my view of it.

“Method” acting was at the time very controversial in the theater world. This was due to misunderstanding as to what was involved, but it was also due to the behavior of some of its advocates who, in contravention to Lee Strasberg’s proscription that the actor must do his best to fulfill a director’s wishes, sometimes insisted that they must take their own path.

In spite of this – or because of it – in those years we thought we were an avant garde, bearing the profession’s future in our hands. It was an exciting time. (A recent L.A. Times obituary of Studio member and author Patti Bosworth called it the Studio’s “ golden era.”)

It was also the era of Senator Joe McCarthy, red-baiting and congressional and corporate “witch hunts.” Actors, directors, musicians writers who were thought to have attended certain meetings, held certain views, were black-listed, i.e., fired or never hired. Red Channels magazine published names of suspectees.

A Studio member friend, Will Hare, whose last name was similar to that of black-listed character actor Will Geer, found he had been painted with the same toxic brush and would not be hired as an actor. He scraped together a living moving furniture. (He asked me once to help.)

(Subsequently, Will was able to resume his career. He also created a successful posh restaurant near Stratford, CN.)

When Actors Studio director Elia Kazan voluntarily testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee, many Studio members were shocked and outraged.

I will not go further into this here. The poisonous political atmosphere of the 1950s has been extensively treated elsewhere. I believe that had I been five or ten years older I would have been among the stricken.

At the Actors Studio, members occasionally developed “projects”: full length plays or scenarios. The best were authorized for public-invitation performance.

Two of these have always been vivid in my memory, both devised by Freddy Sadoff, a dynamic go-getter whom I came to think of as the poor man’s Orson Welles.

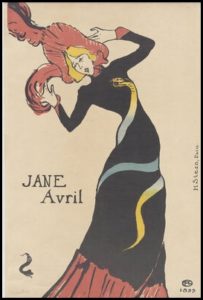

The first was a performer-director-created scenario depicting characters in Henri de Toulouse Lautrec’s lithographs, wood cuts and paintings. (Lautrec’s works were then very popular among young people: his prints hung on trendy elephant-grey-painted walls of every “with-it” aspiring “artiste.”)

In Freddy’s project, actors portraying Lautrec’s Moulin Rouge characters Jane Avril, Yvette Gilbert, La Goulue and others, kicked-up the can-can in chorus-line, and competed for the attention of a piano player who was hidden behind an upright piano, bringing him steins of beer which his hand, arising from an unseen body, would take away. The fidelity of costumes, lighting and makeup to Lautrec’s palette was not less than astonishing.

The other Sadoff production was a dramatization of J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, our generation’s de riguer novel.

In 1953, I was part of such a project: a dramatization of Calder Willingham’s novel End As A Man which portrayed sadistic hazing in a military academy, asking whether indeed this enabled youngsters to embody the title.

Studio newcomer James Dean saw a rehearsal of our project and asked if he could become a part of it.

Director Jack Garfein gave him the part of court stenographer, who with no lines, types the ongoing procedure of the last act’s court martial.

In the last of our public performances, as the last act was nearing, Dean did not appear. Garfein grabbed a Studio member, put him in uniform and had him serve the function. In the midst of that last act, Dean showed up, apologizing that he had been at the beach and forgot. Garfein said, “I will never use that actor again!”

The reception to this Actors Studio effort was so positive that an off-Broadway production was arranged at a small theater in Greenwich Village. Claire Heller, Jack Garfein’s friend, produced.

The ensemble acting was so significantly praised that a Broadway production was scheduled.

Broadway reviews, it turned out, were tepid. The ensemble acting was praised but script weaknesses mentioned in its previous incarnation had not been addressed.

Actors Studio powers-that-be, when planning for a production that would for the first time feature its name, had decided commercial success required star billing.

Ben Gazzara, in the leading role of Jocko de Paris, was given star billing. I, the only cast member who’d previously appeared on Broadway, and non-Studio cast member character actor Frank M. Thomas were “featured.” (Below in the credits and ads.)

I was extremely upset about this. Fueled by jealousy on the one hand and on the other by righteous indignation that the ensemble ideal of all-equal had been violated, I made my feelings known and eventually left the show. George Peppard played Marquales in the later film version.

Claire Heller and I had been an item for several years now and in 1954 we married at City Hall. Albert Salmi and girlfriend Peggy Garner attended.

Late that year, one of the most bizarre – and troubling – experiences of my life occurred during a performance at New York City’s President Theater during a performance of George Bellak’s play The Troublemakers in which I had the lead.

In the second act, my character Stanley Carr was having an argument with the father of Stanley’s girl friend.

In the midst of the scene, a voice arose from the audience:

“Bill!”

We hesitated briefly, then continued.

Again, even louder: “Bill!”

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a figure rise and come down the center aisle toward the stage. I turned to look. It was a young woman: “Bill! Help me! Help me!.”

Transfixed, I watched as she came to the edge of the stage, threw her leg over its lip as though to climb onto it. Something in me vaguely recognized having seen her somewhere; something else was at work in me and I – intuitively? – extended my hand to help her up.

On the stage, she threw her arms around me, repeatedly crying “Help me! Help me!” She was also thrusting her hips into mine.

Stage managers dropped the curtain, rushed out and put arms around her; she allowed herself to be led away.

The curtain was raised; we finished the second act. I had a quick change and rushed to my upstairs dressing room to make it.

The stage manager came to my door. “Bill, she’s locked herself into the [basement] women’s dressing room and won’t talk to anyone but you!”

I ran down to the basement. The “dressing room” was simply sheets of plywood formed into a cubicle with a locked door. The stage manager whispered to me, “We’ve got an ambulance outside. Get her there!”

I told her I had come. She opened the door, pulled me violently inside and locked it, embracing me and repeating her cry.

Outside the wooden door, people are yelling, “Bill, are you alright?” If I turned my head to answer them, she went into a spasm.

I knew I had to be simple and straight.

“I want to help you,” I said quietly, “but I don’t know how. Are you seeing someone, a doctor, a psychiatrist?”

“Yes.”

“We’ll have to contact him. I think there’s a phone-booth on the street. You need to call him.”

“I’ll go if you take me there.”

“OK.”

We open the door, head for the street, the stage manager nodding to me that we all understand the plan.

Outside, after a few steps, the ambulance is in view, and white-coated attendants approach us. The dark-haired young lady turned and looked at me, her betrayer, with a pain and sorrow I will never forget.

Of course the mystified audience had been waiting for the third act to begin. We hurried back to satisfy them.

(Days later, I remembered where I had seen her: at the luncheonette where Actors Studio folk gathered after a session. She had approached and sat in the only empty seat at our table. I assumed she knew someone there, but no one spoke to her, so I made friendly conversation. Even later I was told that, as a friend of the Ben Gazzaras, she had asked them to invite her and me to dinner.

Several weeks after the incident, her psychiatrist phoned me to say she was sorry for had happened. I asked how she was. “She’s making progress,” he replied.)

In these years, Jimmy Dean and I had become friends. We both played recorders and he played the bongo drums. One night we played at his apartment til the neighbors complained, then went first to a late-night hamburger joint til it closed; then played in a commercial car garage – with wonderful reverberation – until 4 AM.

By the time Claire and I had married, Dean had of course become a major film star with “East of Eden” and “Rebel Without A Cause.”

Claire’s parents – her father was a well-to-do stock broker – gave us a post-wedding reception at their home in San Francisco. On the way back from that event, we stopped in Los Angeles and asked through his agent if we could see Jimmy.

He invited us to visit him on the set of “Giant” where we met Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson. That evening he invited us to dinner at one of his favorite Italian restaurants in Hollywood; his date was Ursula Andress.

We had driven to the restaurant in Jimmy’s station wagon. During dinner, a man who was apparently Dean’s insurance agent came over and told Jimmy that he had just bought a Porsche and wanted to know how to drive it in race fashion. Jimmy said, “When we’re through follow us in your car and I’ll show you.”

For those who don’t know, L. A.’s Coldwater Canyon is a climbing, twisty narrow road. The drive we experienced – I can only say that I thought my time on earth might be ending. Turns out it wasn’t.

In 1955, film director Robert Aldrich cast me in Attack!, a treatment of stage play The Fragile Fox. Aldrich did not have me read. He made his decision after an interview in my agent’s office. The film was not particularly well reviewed, though it became much more respected later. My role was substantial – I was given “introducing” billing – but no studio executives tried to sign me to a contract.

In 1955, film director Robert Aldrich cast me in Attack!, a treatment of stage play The Fragile Fox. Aldrich did not have me read. He made his decision after an interview in my agent’s office. The film was not particularly well reviewed, though it became much more respected later. My role was substantial – I was given “introducing” billing – but no studio executives tried to sign me to a contract.

In hindsight, this was perhaps a crystal ball in which my career was foretold. Burton had been wrong; I was not to be a star, but a functioning middle-class actor who had ups and downs, hits and misses.

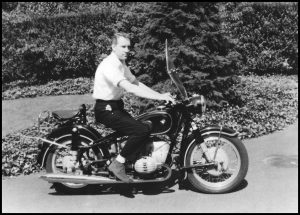

The money from Attack! enabled me, back in New York, to buy a motorcycle.

The day I came home with the new bike, Actors Studio friend Steve McQueen came over to ride with me. We tooled along the city’s Westside Highway, Steve leading on a BSA 650 doing wheelies, me punching along. At the north end of Manhattan, no longer on a freeway, Steve turned off the road into actual woods. We’re talking street bikes here. Steve is thumping along happily. I, with the horizontal pistons of my BMW RW thrashing brush, am eating lots of foliage.

Returning to mid-town, we descended a ramp to street level. As we approached, the traffic light just at bottom turned red. Steve went through it. I hesitated, then did the same. A cop stopped me and gave me a ticket. Much laughter from a few feet away.

In 1957, I was cast as Treplev in an off-Broadway production of Checkhov’s The Sea Gull, starring Betty Field and was fortunate enough to win an “Obie” for the best performance by an actor that year in an off-Broadway play.

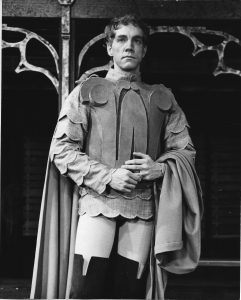

In 1959, I was selected to be in the company at the Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, CT, to play Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet, Demetrius in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and later in the summer, Bertram in All’s Well That Ends Well.

During rehearsal for the latter play, I was served with a note notifying me that I had been fired from that cast. In subsequent years the play’s director John Houseman published a memoir that included deprecating remarks about my ability in that part. I was of course dismayed and puzzled why someone in such lofty position and reputation would make a point of doing such a thing.

I spent that summer at Stratford where rehearsals and performances were given. Claire, a producer on the radio program “Luncheon at Sardi’s,” remained in New York.

In that summer, I began an intense – and illicit – love affair with actress Barbara Barrie. It was a company scandal. Everyone knew about it since I spent more of my days and nights at Barbara’s rented cottage than in my rented room. Of course Claire was puzzled when she came to visit since everyone in the company seemed to avoid us.

Back in NY at season’s end I confessed to Claire and asked for a divorce which she agreed to and implemented.

I moved to a 1 ½-room apartment in the West 80s.

In 1960 I was engaged to play Tom in Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie at the Teatro Tapia in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

David Frank played the Gentleman Caller. He and I got on well and started a friendship that has lasted all our lives. Many years later he, having become an attorney, represented me in a successful legal action against Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. (See our menu listing: “Smithers vs. MGM)

I played Tom again – actually for the fourth time – in a company sponsored by the US State Department as a “good-will” tour throughout South and Central America.

On my 1961 return to the US, I was almost immediately cast by director Dan Petrie in an off-Broadway production of Frank Gilroy’s Who’ll Save the Plowboy? with Actors Studio comrades Jerry O’Loughlin and Rebecca Darke. The play won an Obie that year and Rebecca won for Best Actress.

My English Life

In 1963, I was cast as accountant David Beeston in Terence Rattigan’s play Man and Boy, starring Charles Boyer. Mine was a one-scene role in a British-American cast, scheduled to play first at the Queen’s Theatre, London and later in New York.

For the London rehearsal/performance period, I luckily was able to sub-let a flat in Chelsea’s Nell Gwynn House from an actress going to New York.

In the classical tradition of first-time international travel, I found that exposure to another culture gave me enhanced understanding of my own.

I saw that in shops, titled persons were literally bowed-down to, and that such eminences were in no way embarrassed to say “That cost too much,” which often Americans were uncomfortable admitting. Lords’ and Ladies’ prestige was not based on cash.

I saw that installation of interior plumbing was still somewhat controversial for Brits; that in restaurants/pubs, it was expected that any stranger may sit with you at your table, a distinct rudeness in the US.

Television programming ceased at 11 p.m or midnight. A Sunday morning show could feature a gardener trimming a tree or shrubs – in absolute silence for minutes at a time. Television dramas unfolded more slowly than in the US, emphasizing character exploration and development rather than bang-bang plot motion.

To an American, the English countryside seemed like a picture postcard: lush green fields, farms and pastures in almost geometric arrangements, rather than the rough wildness of much American landscape. I saw that the feathery shape of tree-leaves I had observed in British art, that I had assumed to be fabulous, were evident everywhere.

I found English people always courteous, but very firm, even tough, in their understanding of appropriate behavior.

Since US-style heating was not always present, it was common to wear sweaters indoors.

Wandering through nearby neighborhoods, I saw pharmacy windows plastered with “Room to Let” placards that often specified “No blacks need apply.”

A year in advance of my own countrymen, I experienced Beatlemania; watched Mary Quant mini-skirted “birds”; and viewed on TV youthful antagonism between cycle-riding, leather-jacketed “Rockers” and scrupulously-dressed Lambretta-driving “Mods.”

During that English summer, I accepted a guest-starring role in a television series that would be filmed during the day, permitting me to perform on stage at night. (More about this later.)

The driver assigned to take me to and from the suburban film studio was the son of a Lord. We became friendly, so I felt free In en-route discussions, to ask why he thought Britain would not join a proposed European Common Market (not the EU of today). He replied, “Oh, we’ve always been enemies of France!” I said, “But we and you were once enemies, we’re not now.” “That’s different.” he said. “You were colonies.”

When that guest-role was offered, my British agent cautioned, “British Equity rules require that you have your producer’s permission to do this.”

Following procedure, the agent requested permission from producer Hugh “Binkie” Beaumont.

The reply: “You may have permission if Smithers will pay producer Beaumont an amount of money equal to his fare back to America.”

Everyone who has heard this, then or since, – including British Equity reps – have been thunderstruck!

First of all, it was well known that English actors performing in America were paid much more than their gigs at home, and that American actors in Britain received a fraction of their usual salary.

Beyond that, the vindictive greed displayed was astonishing!

After thinking, I said to the agent,”Screw this! I’m going to do it.” And, as mentioned, I did. The TV salary enabled me for the first time in my life to have some London tailor-made clothing.

Producer Beaumont told British Equity he would deduct the required amount from my Man and Boy actor’s salary. Equity told us, “You understood the terms. There’s nothing we can do.”

In a private conversation, this one-scene actor told Mr. Boyer that he would welcome Boyer’s help in the matter; that he would completely understand if Boyer did not want to be involved, but that if the threat were carried out, he – I – would give notice.

At the relevant Equity hearing, Beaumont’s stipulation was upheld.

He never actually docked the money.

Perhaps my final understanding of English mores was illuminated during my search for a London tailor to accomplish what I’ve discussed.

Man and Boy Canadian actor Austin Willis recommended a Savile Row tailor that he had used. As I entered that establishment, the attendant asked “May I help you?” “Yes,” I replied, “Mr. Austin Willlis recommended you to me. I’d like to have some suits made.”

“What was the name? … Oh, just a moment.” He retired to another room, then came back with a book in his hand. “I’m sorry, sir, but I don’t find that name here.”

“He told me he’d used you before. Don’t you want to deal with me?”

“It’s not that, sir. It’s just that we don’t find that name in our books.” This while looking me steadily in the face.

At the theater that night I told Austin what had happened. “That’s odd.” he said. “Try again. I had them make a naval uniform during the war.”

Back at the establishment, I repeated what I had been told.

“Oh,” said the rep, “that’s a different book!”

Now permitted to the fitting room, I showed a suit jacket I had brought and asked that the lapels be so modeled.

“Hmmm. Two inches wide. That’s hardly a lapel at all, is it sir? We never make them less than three inches.”

“That’s the way it’s done at home. That’s what I want.”

“Let me confer with the proprietor, sir, and see what we can do”

On his return: “We’ll compromise at two and a half inches. After all, people will be seeing it’s our suit you’re wearing.”

I left, and found a more accommodating London professional who gave me clothes I treasured for a very long time.

New York Again

Gradually, life now became darker. Following an independent film that was never distributed, I was for many months cast in nothing. By 1964 my then-agent seemed oblivious to my existence.

For the first time since my Tybalt debut, I had to seek a job in the “real” world to survive.

I found work as a nighttime clerk in a bookstore across the street from Carnegie Hall. Sy, the proprietor, was a great guy. He loved and hired creative people: actors, musicians, writers.

My salary at this bookstore could not sustain me for long however and, in real penury, I asked Sy if he could pay me more.

He then assigned me, at additional hourly pay, to come in early and create an alphabetized file of all plays contained in collections, so that I could show any customer asking for a particular play any anthology that contained it.

Stlil, I was selling furniture to make rent, and still, I had to beg the landlord for more time to make things right.

Then, two whip-smart ladies, who ran their own agency, took me on and life began to take a better turn.

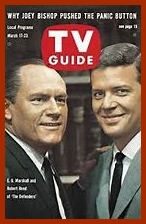

The lady reps negotiated my guest-star appearance in an episode of “The Defenders” TV series, starring Studio actor Robert Reed and E. G. Marshall.

In this series, the stars legally represented accused persons in court and were, of course, winners. To incorporate some degree of realism, however, series scripts sometimes had a prosecutor win.

My role was that of prosecutor, and the script was in the usual vein of triumphant “Defenders.”

Scenes in film work are almost never shot in written sequence, but are scheduled according to other needs: location, time of day, etc.

On this occasion, filming of my character’s summation before the jury was shot early on. I made a few suggestions as to wording or phrases for that summation. They were accepted.

When producers reviewed footage of that scene, they changed the script and edited the film to have my character win the case! So I guess one can chalk this up as one for the upside.

My lady-reps now arranged a trip to Los Angeles to guest-star in an episode of television series “Combat.”

(I still worked at the bookstore, but Sy gave me a leave of absence and asked me to bring back knowledge of how the noted Larry Edmunds bookstore in Hollywood cataloged and arranged its theater books.)

Having finished “Combat,” and literally on the way to LAX airport for return to New York, I had a scheduled interview for a recurring role in the popular TV series “Peyton Place.”

In New York once again, word came that I had been chosen to be David Schuster for that twice-a-week series.

(I made a farewell visit to Sy, and gave him the Larry Edmunds bookstore cataloging system I had gone there to discover.)

So, in that year of 1965, I boarded a westward-bound plane that was never to bring me back permanently to a city that held so many memories.